Unofficially dubbed ‘Chernobyl of the North’, Vorkuta has enough distinctions to make it stand out in its own right. The once-thriving coal town was built by prisoners from the network of camps dotted around north Russia after it had been flagged as a resource trove.

In 1941, the town was connected to the Northern Railway – which initially only ran from Moscow to Arkhangelsk. The 1,200-mile journey took two whole days, spanning landscapes that look like they were painted out on canvas. This figure has remained pretty much the same through the years, despite advances in train production; primarily due to the harshness of the northern terrain.

We (my father and I) travelled on the sleeper trains equipped with touchscreen-tablet menus and USB ports, as well as plastic-wrapped slippers, a towel and a blanket – far cry from the utilitarian locomotives that made the journey nearly a century ago, which featured regularly in the works of Solzhenitsyn and Yerofeev.

More of a surprise came from my father, who’d travelled widely on the TE3 in his youth1. In the perilous years of Boris Yeltsin, those trains had become hotbeds of criminal activity, where ‘urine slopped over the corridor floors and bandity stuck their hands into every pocket and handbag in sight’.

On our trip, we shared the four-bed carriage with two young men – unrelated – who, after some tea and biscuits, kindly coloured our perceptions of life in the north. The most popular locally sourced food in Vorkuta is fish – or grayling obtained from the nearby Kara Sea, an extension of the Arctic Ocean, as well as its surrounding rivers.

Vegetables are a scarcity, but mushrooms come aplenty. Among these are the honey fungus (opyata), foxy boletes (krasno-golovniki – ‘redheads’) and Lactarius resimus (gruzdi) – a popular delicacy in Russia but not found in high esteem elsewhere.

Forgetting my journalistic fundamentals, I failed to record the young men’s names and soon they were completely wiped from my memory. I did, however, jot down their revelations nightly as the train chuck-chucked through the moonlit tundra with a thin LED shining down on my head from the ledge above.

A raft of towns zoomed by us on our northward journey – Kotlas, Sindor, Inta. The train stopped briefly at some, giving us enough time to jump out and grab a tea with a warm belyash.

This part of the world had been palpably affected by the deindustrialisation of the nineties. Factories had been replaced by hair salons, phone repair shops and service-based enterprises. The prime example of this transformation was, unarguably, the last stop on our journey: Vorkuta itself.

As one of Russia’s monotowns, Vorkuta relied on the continuous extraction of coal to keep its economy afloat. When state-owned mines were sold off en masse during the privatisation era, many caved under pressure and, without state support, went bankrupt. This caused a large-scale outflow of residents as many left in search of work elsewhere.

Though some of the remaining mines survived, being brought under the umbrella of VorkutaUgol (Vorkuta Coal) – a joint-stock enterprise – the town’s population contracted significantly, losing roughly a third of its residents between 1989 and 2001.

Now, the population stands at roughly 57,000 – half of its 1989 peak, according to official figures. There is an obstacle to obtaining the true figure: many homeowners reside ‘on paper’ while living and working elsewhere.

Ambitious building projects started during the years of Gorbachev were abandoned shortly after the privatisation campaign began. Their efforts are now marked by the concrete carcasses standing lifeless against the tundra, monuments to an extinguished cause.

Some residents who had remained then are now hatching plans to take themselves and their families elsewhere. Roman, a firefighter and part-time taxi driver, told me he and his family plan to relocate to Belgrade when he qualifies for the early retirement the fire service grants him.

‘They didn’t predict what would happen when the coal ran out. We used to have a meat plant, a poultry farm, a bread factory. It was a sustainable town. Now it’s all decommissioned: they only use Soviet infrastructure, nobody is building anything new.’

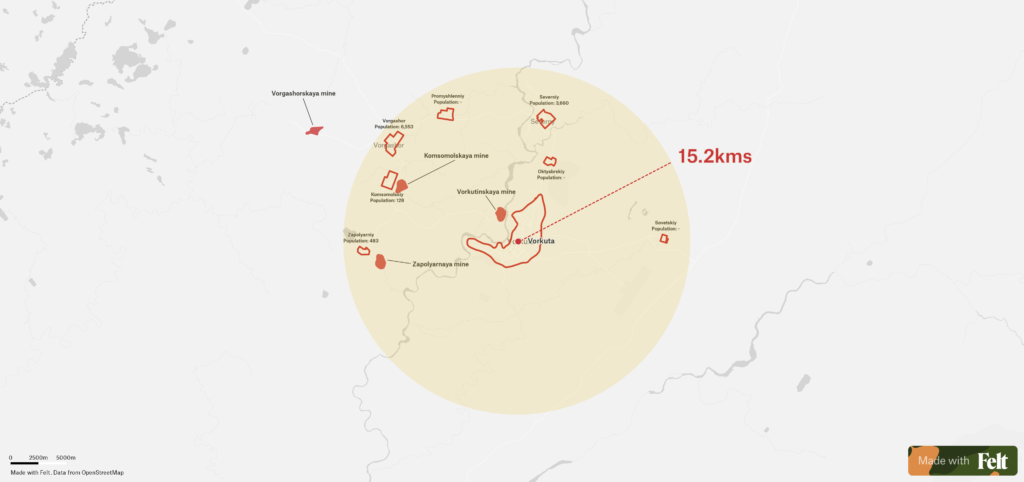

Roman drove us to the nearby settlement of Sovietsky, a neighbourhood that has since closed down due to the high ratio of living units to residents. The government has started a campaign to resettle the families in these far-flung micro-districts closer to the centre of Vorkuta to prevent the wastage of resources required to keep the buildings heated and energised2.

We combed through the derelict blocks, encountering piles upon piles of belongings – books, clothes, the occasional electrical appliance; things left behind in the rush to relocate. Roman said he is constantly called out to extinguish fires set to these buildings by teenagers and vandals.

The gradual erasure of Vorkuta’s settlements poses a stark glimpse into the town’s future (‘Many people come, stay for a while, and leave. It’s the tundra. We want something… warmer’). But many residents remain adamant that this is only the town’s changing of face, and that it will, undoubtedly, survive.

‘The town is not dying. I’ve been here 20 years now and I’m hearing that it’s dying. It’s too expensive to let it completely die out – there are repercussions.’

We met Natalia on a trip to the Vorkuta Museum and Exhibition Centre, where we learned about the humble beginnings of this arctic city (flagged by geologists in 1930 as a prosperous coal basin) and the brutal expansion that followed during the Stalin years (200,000 prisoners were estimated to have died in the cluster of camps known as Vorkutlag, whose populations were used primarily for labour).

Natalia moved to the town from Donbas, eastern Ukraine, during the 1990s, at a time when the town’s jobless masses were fleeing elsewhere. She now works as the museum’s curator.

She gives short shrift to the prophesiers who predict the town’s downfall. Her response indeed hits on something: the harsh conditions of the past 35 years seem to have strengthened the sense of community in Vorkuta.

Making the most of their circumstances, residents have started to organise events – ranging from skiing to indoor sports for pensioners, children’s art classes, and the annual reindeer races, which celebrated their 25th anniversary last year. Run by the indigenous Nenets communities, they gather sizeable crowds from local areas and further afield.

The town’s biggest draw for foreigners, however, remains its eerie brutalist structures, which mark the ruins of vast industrial ambition. To social media influencers, photographers and journalists including myself, they are a stark and incomparable sight. Ironically, they mark the demise that now seems to be spurring the town’s resurrection. The question is can it reverse Vorkuta’s population decline and allow the residents to keep calling it their home for the years to come.

My novel Going to Zossen, which recounts the story of a detention facility director in Vorkuta after the fall of the Soviet Union, will be released in the summer. Subscribe to the newsletter below to get updates.

—

- Before the advent of the Soviet-built 2TE110M, the TE3 was the most produced train in the postwar Soviet Union. ↩︎

- Several of these micro-districts exist. They are located within a 15km radius of Vorkuta town. Some of them, like Oktyabrskiy, have been unpopulated for decades while those such as Sovietskiy held a small population until recently. This was no more than a couple of dozen people. ↩︎