This article first appeared in Newstalk. Its author travelled with the aid of the Simon Cumbers Media Fund to cover statelessness in Sierra Leone. The broadcast below aired on The Hard Shoulder on 20 December 2018.

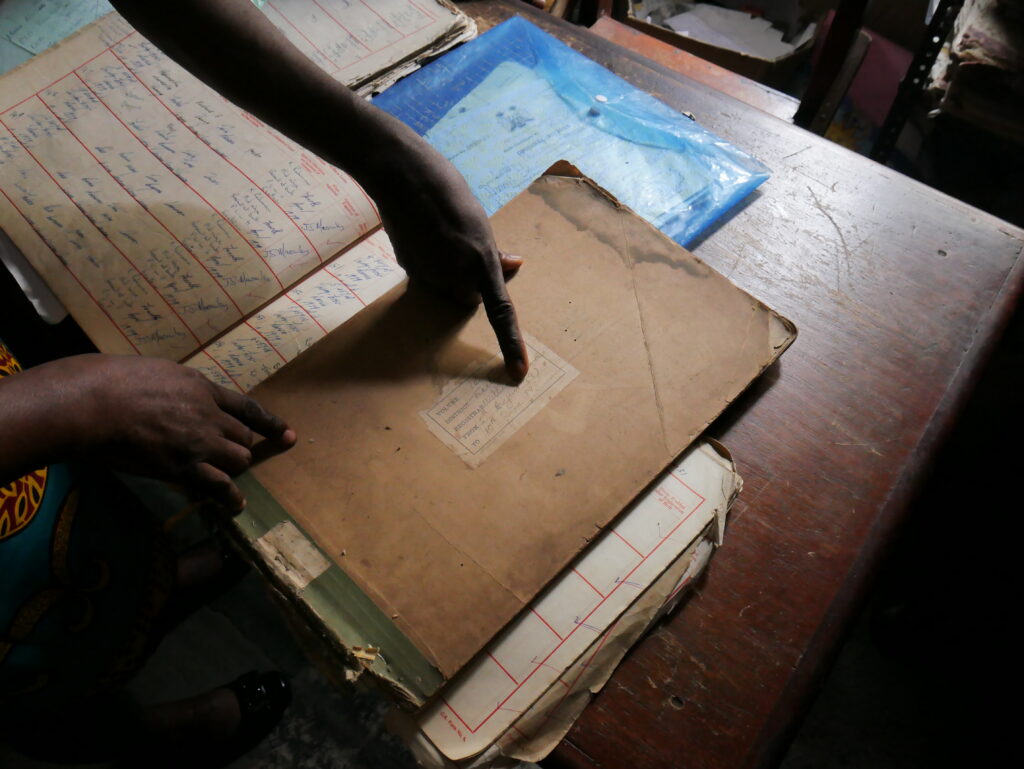

A bar of light falls on the long metal rack against the wall, illuminating a dusty stack of paper archives. A stout figure moves past, eyeing the books with hawk-like precision.

‘Rats,’ he says. ‘They will eat anything for survival.’

Simon Kuyembeh is a principal registrar at Sierra Leone’s Births and Deaths Ministry, an aged building located in the central district of the capital Freetown. He is a record keeper, responsible for guarding the bulk of the country’s civil registrations dating back to the late 19th century.

Simon is among a team of registrars who are currently playing a pivotal role in converting the paper archives into a new digitised format. But they are caught in a race against time – facing a glut of natural and social challenges that pose a risk to their sector’s development.

In the past three decades, Sierra Leone suffered a string of tragedies that ruptured its natural infrastructure. During the brutal ten-year war that broke out in 1991, national registrations were virtually impossible to conduct, leading to an epidemic of undocumented births. Added to this, the country lost a large portion of records during the conflict.

Then, in 2014, Ebola struck, deferring large proportions of the country’s population away from health facilities – leading thousands of women to give birth without medical supervision.

Undocumented children

By 2015 it was estimated that more than a half of the country’s children were undocumented.

‘A birth registration is very often the most tangible link people have with the state,’ says Michael Sanderson, the Regional Protection Officer with UNHCR.

‘If you took out your wallet right now and just laid the cards out on the table, you probably have a credit card, a driver’s licence and maybe an ID card. Already, you’re not really in danger of being lost,’ he says.

‘These establish you as a national citizen – and so there is no question about which state has the responsibility for your protection.’

‘If you’re in West Africa – where you just do not have access to all of these documents in an ordinary way – birth registration becomes exceedingly important. For children, it will be the only evidence that they are who they say they are.’

Statelessness is a known gateway for a litany of human rights abuses. With no documentation to prove age or origin, children are vulnerable to forced marriage, labour and human trafficking.

According to UNICEF nearly 40% of Sierra Leonean women aged between 20 and 24 have already been in a marriage by the time they were 18.

Societal challenges

Following the country’s recovery from the Ebola epidemic, the government carried out a mass registration programme with the help of PLAN International and UNICEF, documenting large swathes of unregistered people mostly in the rural provinces – where the problem was at its worst.

A recent UNICEF report highlights that in the three years since Ebola has been contained, registrations have increased up to 77 per cent. But now the government faces a new challenge – the skills gap.

Simeon says: ‘Most of the staff are not computer literate. Most of us, we were born before computer, so to be able to train in computer applications you have to take some time and it is not easy.’

Training and upskilling existing registration staff on key aspects of the documentation process is critical. But there are also natural factors that threaten the work.

The aged paper archives face an acute risk of deterioration due to pests and the humid air conditions which they are exposed to.

Currently the government of Sierra Leone are finding themselves in an environment where the risks significantly outweigh the solutions. And this is before they tackle the societal and cultural challenges at play.

Literacy rates in Sierra Leone

According to the government of Sierra Leone 70 per cent of the population is illiterate. Furthermore, a large proportion of the country’s population are not educated on the importance of registration.

Koinadugu II is a small hamlet buried in the vast Sierra Leonean bush 200 miles from Freetown. The road from the nearest main village of Kabala, 20 miles west, is a crooked dirt trail that stretches over humps and down hollow ravines. Here, government registrars face their biggest challenge in advocating to local populations the importance of birth registration.

Alimatu Kamara, a midwife at the village’s tiny medical facility, says in the past six months only a handful of women who gave birth returned to obtain their child’s birth certificate.

‘Since I came here, we just had a few of them that have registered,’ she says.

‘This month, one came in that we gave a birth certificate to – because soon after the delivery the man came back with the name that he was supposed to give to this child, so we issued a birth certificate to them.’

‘But it takes us a lot of problems, because they don’t come up with this name on time.’

The registration process

The process of securing a birth certificate requires both parents to come back to the place of birth to log their child’s name in the registration booklet. However, in most cases they do not return.

Aminata Mansaray, a local villager who was displaced during the war, says her documentation was destroyed along with her family’s. Despite being stateless for so many years, she has never tried to obtain another for herself.

‘I was born in Kono and brought here as a child,’ she says. ‘Since then, I’ve been here throughout my life.’

‘I have never gone to school. We had birth certificates when I was young but during the war we lost everything.’

Aminata does not know how old she is. Though she strikes a robust, maturely figure, it is virtually impossible to trace her exact age.

But even without documentation, she says she has never encountered any trouble availing of anything.

‘I have never tried to get one,’ she says. ‘I have not encountered a problem where I would go into a place and they would not give me something. I’ve never had anything like that.’

Under Sierra Leonean law, a person is required to possess a birth certificate to avail of any public service, from education to healthcare. But local authorities rarely enforce the legislation – meaning a sense of necessity is rarely evoked.

‘We do what we call community engagement,’ says Saidu Timbo, district registrar at Kabala’s births and deaths centre. ‘We engage people and tell them about the importance of registering and why it is necessary for them to obtain birth certificates so that they can have interest in registering their children.’

Progress is slow – but it is moving in the right direction. Despite not having any documentation herself, Aminata and her husband obtained birth certificates for their children.

‘For each of my six children, their father helped them get birth certificates,’ she says. ‘Now they all have one.’

And while many grownups in the village don’t have documentation, a lot of their children now do.

Looking to the future

The message echoed by the government and its NGO partners is slowly resonating with the public: there were 41,166 late birth registrations across the country in 2016 – the last recorded year – and these numbers are set to increase.

Two years ago, the government of Sierra Leone established the National Civil Registration Authority (NCRA) – a government body that centralises all of the country’s civil records by harvesting them under one roof. Without doubt the NCRA has significantly progressed the national records system.

One of the NCRA’s key roles is to take over the task of overseeing the work of the Births and Deaths Ministry – a job previously carried out by the Department of Health and Sanitation.

However, designating a specialised government body is only one small step in the modernisation process. The Authority now faces the exponential task of acquiring more materials and training personnel – a monumental task but one they are willing to see to the end.